Chellis Glendinning memoir

Excerpt from Meetings With Remarkable Bohemians, Rebels and Deep Heads, forthcoming, 2014

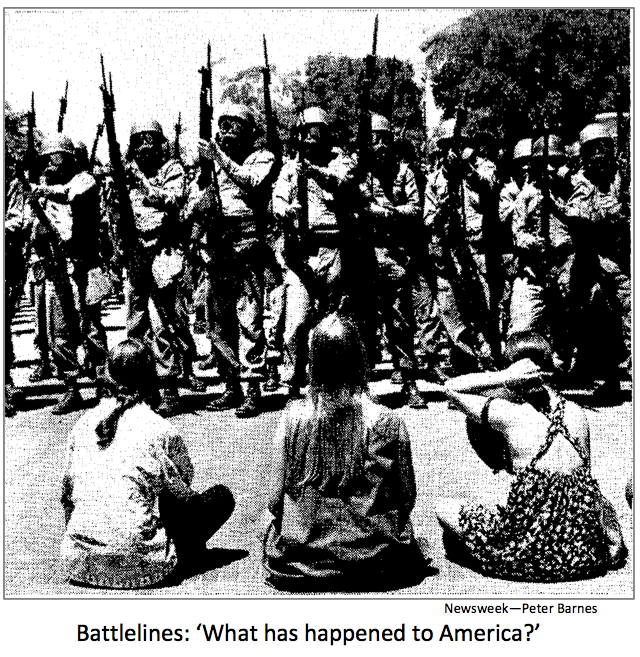

A PHOTOGRAPHER snapped a picture of a line-up of anti-war activists sitting cross-legged under Sather Gate on the UC Berkeley campus—with an opposing line-up of National Guardsmen facing them with bayonets and gas masks. The year was 1969, and perhaps the demonstrators should have taken better notice of the particular gear they donned that day; we at the north end of Sproul Plaza could not see that all the entrances were similarly blocked—and we entrapped within them.

Moments later, in a policing experiment derived from counter-guerilla methods used in Vietnam, a helicopter flew over the plaza spraying C.S. gas. Most of the protesters fell to the plaza’s concrete floor writhing and vomiting, while the Guard moved in to beat the shit out of them. By a stroke of luck, my husband and I fled through the cafeteria and down the spiral staircase to escape into the lower plaza.

The photo appeared in Newsweek the following week. And as the accompanying article reported, “…police have also gone on a riot, displaying a lawless brutality equal to that of Chicago, along with weapons and techniques that even the authorities in Chicago did not dare employ: the firing of buckshot at fleeing crowds and unarmed bystanders, and the gassing — at times for no reason at all — of entire streets and portions of a college campus.”

Nineteen years later, in 1988, I needed a place to stay for a few weeks in the Bay Area. Friends recommended a San Francisco writer who was looking for a house trade in some beautiful place where he could concentrate solely on his work. They gave me Peter Barnes’ phone number. He arrived one day before I left so each of us could explain the quirks of our abodes. Right off, just as the sun was throwing pink and orange streamers across an evening sky, we headed into the desert. According to Peter: “The whole experience was electric. Your house, the desert, you and your amazing wardrobe and car. I was blown away.”

On my next trip to San Francisco, we became lovers. He wrote me afterward: “Now that the dust is settling, I want to say that I still think there was a ‘higher reason’ our paths crossed…I want to plunge (or at least briskly walk) ahead.” At first, we traveled back and forth to see each other. I particularly enjoyed staying at his 28th Street Edwardian in Noe Valley where we were within walking distance of cafés, natural food stores, and movie houses.

We went on a few jaunts in northern California and, when apart, madly wrote letters. Before one such visit, I was getting ready to appear in the film Berkeley in the ‘60’s. The director had told me to bring a photo that could be blown up to serve as a backdrop for my interview. I chose the shot that had appeared in Newsweek in 1969. I pulled out the tattered magazine featuring that photo from my files. The photographer: Peter Barnes. The author of the article: Peter Barnes. The author is on the left with Indian print shirt and braid. The woman to the immediate right is on acid.

After five or six months, Peter confessed he was “not in love with me.” I was surprised but taken by his candor, and so what could I do? We morphed into life-long friends. As of this writing he and I have been linked by a political tableau for 45 years, by friendship for 26.

PETER IS a gentle soul, a vulnerable man who questions himself at every turn, yet has the courage to live in a state of spiritual wonder and carry through his passions to completion. Plus, he is rakishly handsome. He is also one of Harvard’s post-Beatnik, early ‘60’s graduates, which also include Adam Hochschild, Todd Gitlin, Elizabeth Holtzman, all of whom have made key contributions to U.S. social-change movements. Read: Peter is a Deep Head.

And he has made much of his intelligence. He grew up in New York City, the oldest of two children of Leo and Regina Barnes. Leo’s parents had emigrated from Odessa to the United States in 1905. Regina’s had traveled to the U.S. from Bucharest, Romania. Leo was an economist, Regina an English teacher at the High School of Music and Art where she helped organize the teachers’ union. They saved enough money to send their son to Harvard, where he graduated summa cum laude in history, later earning a master’s in government at Georgetown.

From 1966 to 1970 Peter worked at Newsweek in a position he likes to call “their house lefty.” He went on to be the West Coast correspondent for The New Republic. He also wrote a book that was daring for its time: Pawns: The Plight of the Citizen-Soldier (1972), illustrating that soldiers are not, as some of us erroneously saw them during the Vietnam War, nasty perpetrators of war, but rather the pawns and victims of higher perpetrators.

In 1976 Peter co-founded a worker-owned solar energy company, The SolarCenter — but after Governor Jerry Brown and President Jimmy Carter were replaced by Republicans, tax breaks for solar energy were eliminated and the entire industry collapsed. He then co-founded one of the first socially responsible money funds, Working Assets, later adding a credit card that donated to social justice, environmental and human rights groups every time a cardholder purchased something.

As an originator of Working Assets, he humorously referred to himself as a “pretend banker.” By the early ‘90’s, he could have added “pretend telecommunications entrepreneur.” In 1982 the monopoly of AT&T was broken up and Peter set out to form his own phone company. As a friend, I would receive late-night phone calls while he was trying to convince investors to risk money on what deep inside he suspected was a hair-brained project. “I must be mad!” he would moan from a hotel room somewhere. “They’re going to think I’m crazy. I am, I am!”

Working Assets Long Distance turned into a financially successful alternative for people with a social conscience — with a portion of each phone call going to political groups. In 1995 he was named Socially Responsible Entrepreneur of the Year in northern California.

IN THE MID-1980’s Peter felt the urge to become a father. Still reflecting the Bohemian tone of the’60’s, all manner of possibilities to go about such an endeavor were exploding in San Francisco’s neighborhoods. Threesomes were living together, gay men raised sons and daughters, serial monogamy was popular, open marriages abounded. Peter got together with a lesbian living down the street, Pam Miller; he provided the sperm and Pam gave birth. Zachary was born in 1987. He began his life going back and forth between Peter’s and Pam’s houses, with a bedroom he could call his own in each.

Peter liked being a father. In 1998 his then-wife Leyna Bernstein got pregnant, and Eli was born.

As he approached 60, Peter was struck by yet another electric idea. Pulling together the threads of his intellectual life, he wrote Who Owns the Sky? in 2001. His answer to his own question was that all of us own the sky together, from which it follows that we can limit the amount of carbon polluters put into our air, charge them for putting it there, and return the proceeds to everyone equally.

The work thrust Peter into the public forum in a new way. He promoted his “sky trust” idea in the halls of government, and bills were introduced in the House and Senate to create such a system in the U.S.

After that he penned another visionary treatise, Capitalism 3.0: A Guide to Reclaiming the Commons. Unlike many of his cohorts who see capitalism as beyond redemption, Peter believes it’s fixable and worth fixing. Its two tragic flaws — ever-widening inequality and never-ending destruction of nature — can both be fixed by charging for private use of common assets such as ecosystems and paying equal dividends to everyone.

One thing can be said for sure. For all his shyness and self-doubt, Peter Barnes is a thinker of one-of-a-kind ideas and adept at using them to stir things up. And he’s definitely over the writer’s block he perennially claimed to suffer from.

Yet another book popped out in 2014: With Liberty and Dividends for All: How to Save Our Middle Class When Jobs Don’t Pay Enough. Conceptually an extension of his previous books, it argues that America’s large middle class needs non-labor income as well as jobs if it is to survive the twenty-first century. And from whence might such non-labor income come? From charging corporations when they use common wealth and paying dividends to everyone.

Peter writes,“Would dividends from co-owned wealth mean the end of capitalism? Not at all. They would mean the end of winner-takes-all capitalism, our currently dominant version, and the beginning of a more balanced version that respects all members of society, including those not yet born. This better-balanced capitalism — perhaps we could call it everyone-gets-a-share capitalism — wouldn’t solve all our problems, but it would do more than any other potential remedy to preserve our middle class, our democracy, and our planet.”

AS THE YEARS rolled by, Peter became financially stable, and he realized a dream: he bought land along Tomales Bay north of San Francisco. The idea was not just to have his personal sanctuary, but to offer it as a haven for writers who otherwise would not have unobstructed time to concentrate fully on their creations.

Peter quotes poet Mary Oliver: “No one has yet made a list of places where the extraordinary may happen. Still, there are indications. It likes the out-of-doors. It likes the concentrating mind. It likes solitude. It isn’t that it would disparage comforts, or the set routines of the world, but that its concern is directed to another place. Its concern is the edge, and the making of form out of the formlessness that is beyond the edge.” And he goes on to say: “I have seen time and again how true these words are — how a few weeks of ‘writing on the edge’ can be transformational for emerging writers and rejuvenating for established ones.”

He built little sheds overlooking the bay as it reached north to the Pacific Ocean—and in 1997 began the Mesa Refuge writers’retreat. Residents since then have included Michael Pollan, Terry Tempest Williams, Daniel Ellsberg, George Lakoff, Rebecca Solnit, Frances Moore Lappé, Wes “Scoop” Nisker, Wolfgang Sachs, Carl Anthony, and — so far — over 600 other established and budding writers.

Free distribution with attribution

Free distribution with attribution