An Outcry: Thoughts on Being Tear Gassed

Newsweek, June 2, 1969

LAST TUESDAY, I was gassed twice in Berkeley. It hurt. The police and National Guard no longer bother with simple tear gas. They are using a chemical called CS — the kids call it pepper gas — that the Army uses in Vietnam. It not only stings the eyes but sets fire to the nose, mouth and throat, and made me, at least, feel groggy and mildly nauseated.

Many other people, of course, got hurt far worse than I did. They were clubbed and shot as well as gassed. One 25-yearold onlooker was killed by buckshot pellets the size of a marble. So this is not in the nature of a personal complaint; it is rather an outcry against what is happening in California, and by extension, what is happening to America.

In many ways, the violence of the past few days in Berkeley is more frightening than the violence that exploded in Chicago last August. In Chicago, as the Walker report concluded, the police erupted into a riot. But at least no one was killed, the national media told the story to the world and, among his critics and defenders alike, Mayor Daley was held responsible for the cops’ behavior.

In Berkeley, under cover of Governor Reagan’s three-month-old “state of extreme emergency,” police have also gone on a riot, displaying a lawless brutality equal to that of Chicago, along with weapons and techniques that even the authorities in Chicago did not dare employ: the firing of buckshot at fleeing crowds and unarmed bystanders, and the gassing — at times for no reason at all — of entire streets and portions of a college campus.

The Berkeley rioting could perhaps most accurately be described as an outbreak of class warfare between cops and students. To the cops, the young and shaggy-haired denizens of Berkeley have become “niggers,” subject to clubbing and gassing for what they are, rather than for anything they might have done. To the students, most policemen have become “pigs,” brutish representatives of a power structure so up tight it could not even cope with the spontaneous creation of a “People’s Park.” Few students actually threw anything more dangerous than epithets, but a sizable number, goaded by gas and gunshot, were increasingly willing to be led into cat-and-mouse tactics of guerrilla provocation.

Unlike Chicago, the lines of political authority in Berkeley have been so confused that it has been almost impossible to affix direct responsibility for the violence — or, more important, to discover avenues for bringing it to an end. The mayor of Berkeley and the Berkeley police chief have had little control over the situation: the forces present have included Alameda County Sheriff deputies, the California Highway Patrol, the San Francisco Tactical Squad, the National Guard, and police from Oakland and other neighboring communities — none of whom is responsible to Berkeley authorities. Berkeley Chancellor Roger Heyns, whose initial misjudgment turned the People’s Park into a battleground, has lost control over the forces of “law and order” on his campus.

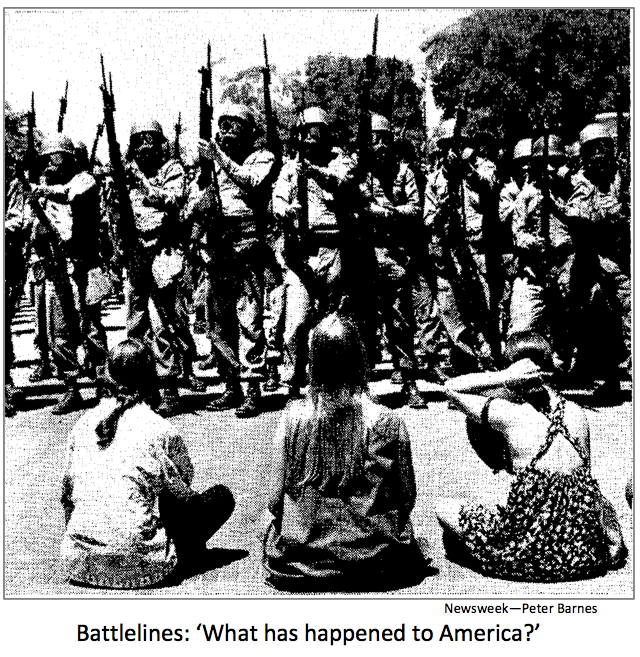

FOR SEVEN DAYS IN MAY, the effective rulers of this occupied city and university were 3,000 unknown men in uniform, headed by two generals and a sheriff playing war games with real people’s lives. In the end, however, one man — Gov. Ronald Reagan — is responsible for what is happening. He is the only man who can stop it now and — in terms of the popularity he has gained from it for the moment — he is its only beneficiary. Far from the scene of his officers’ violence, he has projected himself as the virtuous foe of an insidious clique of unruly revolutionaries.

Reagan’s approach is far more sophisticated than Joe McCarthy’s and, in my view, far more ominous: Joe McCarthy never controlled the National Guard, nor did he contribute to the polarization of our society with bloodshed.

The real danger in California isn’t the students, nor the tree-planting street people, nor even that handful of genuine revolutionaries that Reagan so piously condemns. It is the uncontrollable use of paramilitary force without responsibility: it is the helplessness of such representative institutions as the Berkeley City Council (whose meeting during the violence was a charade); it is the fearful reluctance of moderate public officials to speak out.

No one denies that there is a group of revolutionaries in Berkeley and throughout the country who are determined to provoke confrontations. No one questions the fact that tens of thousands of American students feel alienated from society as they see it. But you do not diminish alienation or defeat a hard core of revolutionaries by gassing and clubbing and shooting indiscriminately.

Quite to the contrary, such a primitive response only plays into the revolutionaries’ hands and takes attention away from specific issues that are negotiable and should be negotiated. The olive-drab National Guard helicopter that sprayed pepper gas over the campus may have cleared Sproul Plaza for twenty minutes, but it radicalized hundreds of non-revolutionary, nonviolent students for far longer than that, and did little toward settling the controversy over the People’s Park.

While the escalation of armed force undoubtedly benefited Reagan politically and gave some policemen and militant students a chance to prove their virility, it did no one else any good at all. What was called for in Berkeley—whatever the provocation—was not pepper gas, buckshot and bayonets, but reason, restraint, and as much good faith as possible.

Beyond the smoke and confusion of last week’s tragic events in Berkeley are some broader questions. When youthful citizens can be wantonly gassed and beaten, all because of a small, unauthorized park, what has happened to America? What has happened to our sense of perspective, our tradition of tolerance, our view of armed force as a last — never a first — resort?

Free distribution with attribution

Free distribution with attribution