Bad Day at Black Mesa

The New Republic, July 17, 1971

IT HAS BEEN A CONVENIENCE for white immigrants to lump all native Americans together as Indians, though most of the peoples we call Indians are as different from one another as Greeks and Swedes. They have different origins and histories, speak different languages, worship different gods and follow different lives. None has more fascinating traditions or a more appealing world-view than the Hopis of the arid Southwest.

Oraibi, the Hopis’ spiritual capital, sits atop a 600-foot escarpment in the middle of the Arizona desert. A paved highway passes about a quarter of a mile away, and a dirt road leads to the village edge. There’s nothing physically attractive about the place — many of the adobe buildings are in disrepair, rusting car hulks are strewn about, and color is notably absent — yet there’s something here that immediately arouses a feeling of awe. Perhaps it’s the landscape’s evocation of the holy lands around Jerusalem; or the vista south toward the San Francisco peaks, where Hopi spirits are said to reside, like Greek gods upon Olympus; or the knowledge that this is the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States.

The first house as one enters Oraibi belongs to the kikmongwi, or spiritual leader of the village, Mina Lansa, and her husband John. Mina’s father, who was a kikmongwi before her, once told her that Hopis have lived in Oraibi and on neighboring mesas for 3,000 years. History books put the date of settlement at around 1100 A.D.

Every morning John Lansa walks from his village on the mesa to a farm in the desert below, a remarkable farm whose soil runs through one’s fingers like sand, that uses no irrigation, no artificial fertilizers, tractors or pesticides. Here John grows corn, beans, watermelon, squash, grapes and peaches, carefully surrounding each seedling with rocks to provide protection from the wind. By planting just in the right places, and at just the right times, he takes advantage of every drop of water that collects beneath the surface. “If rain comes,” he says softly, “the crops will be good. But there is so much trouble…”

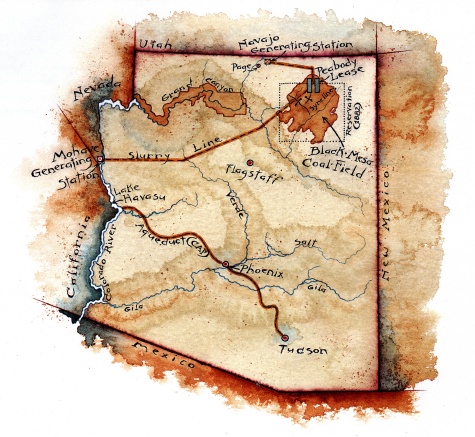

Hopis talk a lot about trouble these days. There’s the severe drought that has stricken the South- west, a consequence, Hopis say, of white man’s disrespect to mother earth. There is dissension within the villages, and between the generations, that worries many Hopi elders. Most disturbing of all is what is happening on Black Mesa, just to the north of the Hopis’ villages and farms. Here the Peabody Coal company has flattened roads, brought in steam shovels, drilled wells for slurry and begun digging out the largest strip-mine in the world, selling the coal to a consortium of power companies who burn it to produce electricity for Los Angeles, Phoenix and other booming cities of the Southwest.

Hopis talk a lot about trouble these days. There’s the severe drought that has stricken the South- west, a consequence, Hopis say, of white man’s disrespect to mother earth. There is dissension within the villages, and between the generations, that worries many Hopi elders. Most disturbing of all is what is happening on Black Mesa, just to the north of the Hopis’ villages and farms. Here the Peabody Coal company has flattened roads, brought in steam shovels, drilled wells for slurry and begun digging out the largest strip-mine in the world, selling the coal to a consortium of power companies who burn it to produce electricity for Los Angeles, Phoenix and other booming cities of the Southwest.

Part of the Hopis’ fear is that the strip-mining operation will upset the delicate water tables that have sustained their desert farms for nearly a millennium. Beyond this is a deeper concern that what is being done now to Black Mesa is merely the culmination of decades of white man’s foolishness. For much too long, Hopis say, we’ve been cutting up the earth, destroying her innards, and grievously upsetting the harmony of living things. This process, they are afraid, will lead not only to the destruction of the Hopis’ way of life, but to the death of us all.

Understanding the Hopis isn’t easy. They use none of the scientific terms we are accustomed to, but speak almost mystically, with the wisdom of a people whose survival in a barren desert has quite literally depended upon harmony with the elements. In the Hopi religion, which is inseparable from their daily lives, all things —including the earth — are alive. Massau’u, the Great Spirit, gave to the Hopis the responsibility of protecting life, warning them that the task would not be easy. Dances and ceremonies would be necessary to keep living things in balance, to insure that rain would come forth and that crops would bloom. It would also be necessary to live humbly, taking from mother earth no more than was needed, and always giving to her as well as taking.

In accordance with their religion, the Hopis have for centuries been “decidedly pacific in character, opposed to all wars, quite honest and very industrious,” the first U.S. Indian agent in the Southwest reported in 1849. A century later, the Selective Service System ruled that any Hopi who so desires may automatically be classified as a conscientious objector. Hopis have shunned competitiveness and the urge for power and wealth. Village leaders have labored in the fields and shared the same living standards as all other tribal members.

Still, many Hopis believe they have failed in their historic task, for they have not protected the earth from the ravages of others. Three times before, according to Hopi myth, the world has been destroyed because greed and war got out of hand. Each time Massau’u gave man another chance, and each time man again went astray. Now we are living in the fourth world, and it may well be the last.

“The prophecy says that there will come a time of much destruction,” says John Lansa. “This is the time. The prophecy says there will be paths in the sky. The paths are airplanes. There will be cobwebs in the air. These are the power lines. Great ashes will be dumped on cities and there will be destruction. These are the atom bombs America dropped on Hiroshima. The prophecy says men will travel to the moon and stars and this will cause disruption. It is bad that spacemen brought things back from the moon. That is very bad.”

NOT ALL OF THE 6,000 Hopis agree with John Lansa. For the better part of a century the tribe has been split into feuding factions — the so-called Progressives favoring adoption of many white man’s ways, the Traditionals holding firmly to the ancient path. In 1906 Traditionals and Progressives in Oraibi fell into a dispute over whether Hopi children should be allowed to attend U.S. government schools. A pushing match was arranged to resolve the quarrel, with villagers of each persuasion deployed on opposite sides of a line. After several hours the Progressives proved to be the stronger pushers, so the Traditionals packed up and founded a new village, Hotevilla, a few miles to the north. Shortly thereafter U.S. Army troops arrived in Hotevilla, snatched away Hopi children to government boarding schools and imprisoned village leaders who resisted.

Three years ago Hotevilla itself divided over the issue of electricity. Progressives, backed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, called in the Arizona Public Service Company; Traditionals threw themselves in front of the company’s trucks. In the end the Traditionals prevailed, and Hotevilla remains one of three Hopi villages without electric power.

Equally divisive was the issue of political organization. Hopi villages had for centuries been self-governing city-states, with no central authority over the tribe. This was unsatisfactory to the federal government, which found it difficult to deal with such a diffused power structure. A Hopi constitution was drawn up by the BIA in 1935, under which each village would send representatives to a Tribal Council. Progressives welcomed the constitution and have dominated the Tribal Council ever since. Traditionals simply ignored it, claiming that the Hopis had never been defeated by the Americans, had never signed a treaty, and should not recognize the US government. Several Hopi villages still refuse to send delegates to the Tribal Council, and most kikmongwis refuse to certify Council delegates, as the constitution requires.

The forces working against the Traditionals today are stronger than ever. There are, of course, the old menaces — BIA schools, Christian missionaries, and electricity (which brings in TV and “ties you into the white man’s system”). Now comes the strip-mining of Black Mesa, which not only threatens the Hopis’ farms and livestock, and thus their economic independence from the white man, but also makes a mockery of their sacred responsibility to protect the earth. In addition, Peabody’s contract for Hopi land, coal and water brings to the Tribal Council about $1 million a year — a trivial amount from Peabody’s standpoint, but more than enough to tip the Hopi balance of power in favor of the Progressives.

So, in desperation, the traditional Hopis have appealed to the white man’s government, a government they do not trust. Last month 62 spiritual leaders and kikmongwis, including Mina and John Lansa, filed suit in federal court, alleging that the contract between Peabody Coal and the Tribal Council was unlawfully approved by the Secretary of the Interior. Among other things, the suit contends that the Tribal Council which signed the lease was illegally constituted, since it lacked a majority of members certified by the village kikmongwis.

Attached to the legal arguments was a short statement to the American people: “We, the Hopi religious leaders, have watched as the white man has destroyed his lands, his water and his air. The white man has made it harder and harder for us to maintain our traditional ways and religious life. Now — for the first time — we have decided to intervene actively in the white man’s courts to prevent the final devastation. We should not have had to go this far, but our words have not been heeded. This might be the last chance…The hour is already late.”

Driving west from Oraibi, along a highway flooded by power lines, one is struck by a sense of irony and tragedy. A small but proud people, with the oldest intact culture in the United States, is being overrun — not by force of arms, not by drought or disease, not by the blandishments of schoolteachers or priests, but by white America’s insatiable appetite for electric toothbrushes and air-conditioned buildings whose windows are permanently sealed. Hopi culture is perfectly capable of absorbing certain forms of progress; most Traditionals, for example, use bottled gas for lighting and refrigeration, drive automobiles and possess transistor radios. Education, too, is increasingly seen by younger Hopis not as a threat to traditional values but as a means for acquiring the knowledge necessary to protect ancient ways.

The kind of progress Hopis can’t absorb is that which makes them dependent upon white man’s jobs or welfare, destroys their attachment to the earth, and profanes their religion — precisely the kind of progress America now seems determined to force upon them. The tragedy lies not only in our readiness to commit cultural genocide, but in our inability to listen to a people who’ve been around a lot longer than we have, and may know something we don’t know.

Free distribution with attribution

Free distribution with attribution