Conversation with Jacob Needleman

KWMR, December 19, 2013

Needleman: Well, Peter, I have been looking forward to this conversation with you for a long time. Since I came here under your wing, in a way, as a resident at the Mesa Refuge — a little piece of paradise that you make available to some of us — I’ve been wanting to speak to you about your life, your interests, and start from there. So, I welcome you to this show.

Barnes: It’s very nice to be here, Jerry. I’ve been looking forward to a conversation of this sort as well.

Needleman: So I would like to invite you to start with where your heart is now in terms of your work.

Barnes: Right. Well, my heart and my brain and much of the rest of my body are currently in the process of finishing a book, which is titled With Liberty and Dividends for All: How to Save Our Middle Class When Jobs Don’t Pay Enough. So I will talk about that. But that book is the third of a trilogy, an accidental trilogy, which started about ten years ago with a book called Who Owns the Sky?, where I asked a sort of Zen-like question about something which nobody thinks about really: who owns a lot of stuff that doesn’t seem to be owned by anybody? But if it were owned in a certain way by all of us together, a lot of things would change. So that was what I started exploring ten years ago.

Jacob Needleman

I wouldn’t claim it was a widely read book. It was about climate change, ultimately. Because I was arguing that if we claimed the sky as our own and treated it as property, we could tell potential polluters, “No trespassing!” Or, “If you want to trespass, you have to pay a rising amount of money.” Something like that would be a nice, market-based solution to climate change. And the money that polluters paid would go to all of us, one person, one share, as equal inheritors. I hate to say “owners,” because it raises a lot of red flags, but inheritors of the atmosphere — then we have another nice benefit, which is a more equal distribution of income.

So tying together saving the environment with increasing the equality of the income our economy produces — those have always been twin themes in my thinking and in my writing and in my work. And that led to a second book a few years ago called Capitalism 3.0, in which I tried to envision an upgraded operating system for capitalism. Just as Microsoft brings out a new version of Windows every few years, it’s about time, I thought, that we had a new operating system for capitalism. And if we could do that, what would be the changes? And a lot of what I envisioned was reclaiming stuff that belongs to all of us. Protecting it. Seeing ourselves as joint inheritors and joint creators of most of the wealth around us.

So often we think of wealth as just something that private individuals or corporations create. And therefore, “Oh, they can get as rich as they want because they do us this great service to by creating all this wealth.” My point is that, in fact that is not the case. Most of the wealth that surrounds us is given to us or co-created by all of us together through society, through institutions, and so forth.

Entrepreneurs — of which I’ve been one, so I speak from some personal experience — entrepreneurs perform a very useful function for which they should be rewarded. I’m all for that. But what also happens is that certain people insert themselves in the economy in such a way that they can extract most of the wealth that really belongs to everybody. And that is why the rich get richer and the rest of us are having a hard time making ends meet.

My latest book started off as a book about how to harmonize capitalism with nature. What we call nature is really a very complex system with many subsystems and hierarchies and a sort of meta-system on top of it all that has been called Gaia, the combination of our planet and its biota. The trouble is that capitalism doesn’t pay any attention to this larger system within which it operates, and that is a fatal flaw. So how to make these complex systems harmonize has always been something I’ve been trying to figure out. And that was part of the 3.0 operating system. It includes a mechanism for harmonizing these two these systems. I could explain it in more detail if you are interested.

This third book, though, evolved during the course of my writing because lots of things were going on: the financial crisis, Occupy Wall Street, and so on. Everybody is suddenly realizing that capitalism has a number of flaws. One, which we talked about, is its mindless destruction of nature to the point where it is threatening everything. Two, it doesn’t distribute wealth very well. It produces a lot of stuff — it’s great at that. We have to give it credit where it’s due. But on the distribution front, you know, capitalism is really bad and it keeps getting worse. There’s something inherent in it that makes it go from bad to worse.

There are a few other lesser flaws, as we saw with the financial crisis in 2008, such as this casino that sits above the real economy, that goes up and then crashes and goes up and then crashes. A lot of people suck a lot of money out of it, but it doesn’t do any good overall for the economy. And it puts us all at risk for no good reason. So we have to do something about that.

And the sad thing was, in 2008 there was a crisis. The flaws in the system became absolutely evident to everyone. We had a President who appeared as if he was going to fix some of these problems. And yet, we came out at the other end with nothing, essentially. You know, we have something called the Dodd-Frank bill, which is supposed to rein in the big banks, but everybody knows it’s a joke.

We certainly haven’t done very much with climate change since Obama got elected, and inequality just keeps getting worse. So, we had an historic opportunity in 2008 and we blew it. And the purpose of the book I’m writing now became to think ahead. We know another crisis is coming. We don’t know when and we don’t know exactly what will trigger it, but we do know it is inevitable. And the question is, how are we going to respond? How are we going to prepare? So that is what I am trying to lay out here.

We know we can’t fix the system now. There is too much dysfunctionality in everything that’s going on in Washington. So we could drive ourselves crazy trying to get something out of the current situation. Or we could think ahead into the adjacent possible and see if we can’t get ready for it. That is what I argue in my book. I’m trying to provoke a discussion about what to do after the next crisis in our economy, with the goal of fixing capitalism so it doesn’t run us into the ground in the ways that it is currently doing.

Needleman: It is an exciting vision as you express it, so fresh and bold. And yet, something different is happening in this century, or the last century too, about our relationship to nature and capitalism. This harmonization of Gaia and the economic system of mankind. Of course, you can’t just be talking about America, but about the whole planet, actually. But of course, we can start with America, I suppose. I haven’t ever heard that particular ideal in that kind of an expression. And suddenly it seems not only obvious that it is needed, but imperative.

Barnes: Yes. And here is an interesting metaphor. James Lovelock, the English scientist who is the father of the Gaia theory, was challenged by other scientists who said, “Well, you know, you are saying Gaia, this meta-system of living and non-living things, is smart enough to self-regulate so that it keeps the climate at a certain level. And it keeps salinity and it does all these things without a divine creator, without a master plan. It just stays in balance, all by itself. “How can that possibly be?” they say. “It sounds mystical or magical or something. There is nothing scientific about it.”

Lovelock’s response was to develop a computer simulation, which he called Daisy World. He hypothesized two different species, black daisies and white daisies, living in a hypothetical environment that is very similar to the earth. And the temperature in this model would go up 25 percent, just the way the actual earth has, because the sun has been warming up for the last 4 billion years. And then he said, “Let us see what happens.” And because these two different species had slightly different heat-reflecting properties, the amazing thing was that as the temperature of the sun went up 25 percent, the temperature of the surface of the earth stayed almost constant, because the species would propagate in different ways to regulate the temperature. And none of the species doing this was consciously trying to regulate the overall system temperature. They were just following their own little rules to replicate and so forth.

But this system as a whole balanced itself beautifully. And there is a whole theory about complex systems and how they have these emergent properties that nobody can actually explain but they do emerge.

Needleman: They do.

Barnes: When you put hydrogen and oxygen together, water emerges. How does that happen? Magic, but it happens.

Needleman: Also, we have a very interesting, almost infinitely complex, self-regulating, extraordinary system right here; two or three or four of them are in this studio now.

Barnes: Indeed.

Needleman: Homeostasis.

Barnes: Homeostasis.

Needleman: A miracle.

Barnes: Right.

Needleman: And we can’t imagine the complexity of this thing.

Barnes: Well, just take our human body with its homeostasis and multiply and magnify it and you have got…

Needleman: A planet.

Barnes: A planet, right. And then there is capitalism, which operates within this Gaia system. Takes a lot of resources and dumps a lot of waste into it and mucks things up all over the place like a maniac. It is clearly not in harmony with the larger system. And so, the question is, is it possible to harmonize it? Do something to it before it is too late? And my answer is, theoretically, “Yes.”

Whether it is actually going to happen, that is a whole other question. But, in theory, I go back to the black daisy/white daisy model that Lovelock created. I am saying, the way homeostasis emerges is by having multiple agents each doing their thing. Nobody is thinking about the whole. It is kind of like Adam Smith. He said, you know, if these little bakers and so forth do their thing, the whole system clicks. And there is a benefit that arises from the whole system. And in capitalism as we know it, we have got black daisies. The way I see it, we have black daisies, but we don’t have enough white daisies. We have hardly any. And so, the black daisies are running rampant and the temperature is going up and all these bad things are happening.

So one way to deal with this is to create more white daisies and put them out in the marketplace. Put them out playing with the black daisies in such a way that they balance each other. They self-regulate when they are both out there. So that is essentially what I propose — that we create trusts, which are legal entities like corporations. They have powers. They are self-perpetuating, self-governing, and so on. But the difference between a trust and a corporation is that the trust is responsible to beneficiaries. It is not a profit-maximizing, share-holder-serving, entity like a corporation is. If you want to send your grandchildren to college, you set up a trust. And the trust’s responsibility is to your grandchildren, to do everything it can to benefit the grandchildren.

So if we set up trusts that manage the atmosphere or watershed or Tomales Bay or any ecosystem that belongs to everybody — if we had trusts that represented these ecosystems, they would say to the corporations, “No,” “Sorry,” or “That is our property.” So very little of this involves government. This all happens in the market, a kind of self-regulating market. Because while I myself am a New Deal Liberal and I believe in government, I do accept as a political reality that there is a lot of resistance to government in the United States. And it shows up, as we are seeing now, with a kind of stalemated government. Government really can’t act the way one might desire. And I don’t think that this problem is going away any time soon. So it would be better if we could get the market to run itself better in the first place so that we needed the minimum amount of government regulation and taxation and spending and all the things that government does.

The other thing these trusts would do, if they charged for use of nature, would be to distribute the income to everybody equally. So there we get to the topic of my current book about paying dividends to all from wealth that we all share but haven’t organized properly yet. And I am saying that if we organize this wealth, which really is ours, in the proper way, we will, first of all, be able to preserve our middle-class because everybody will get some income from that wealth. Not an enormous amount of income, but enough to keep the middle-class above the poverty level in the absence of high-paying jobs. And second, we’ll also deal with the harmony with nature problem. So you have a win-win, self-regulating kind of system. And it doesn’t involve a lot of government. But we do need government to set it up in the first place. So at some point, we are going to have to have a political breakthrough.

Needleman: That is fascinating. What an idea. Capitalism at one point was a beneficent vision and it was correcting a wrong. And then, it went wrong somewhere. It slipped into something else, into making these unnecessary things, increasing desire, increasing the hysteria and tempo of getting and threaded with lies about what is good for our happiness and improvement. And people woke up and began thinking, “I have got everything I wanted, but how come I am so empty? How come my life is meaningless?” And your Capitalism 3.0 was an attempt to adjust that and correct that with the guidance of Dr. Seuss.

Barnes: Yes. Right.

Needleman: Who is probably a good a god as you could have.

Barnes: Absolutely.

Needleman: And so the human element comes into the question of such incredibly big and beautiful visions. I know you have an interest in spiritual thought as well as economics. How do you deal the human element that comes into any attempt to make a difference at a certain point? Say Occupy, for example. At a certain point, the environment movement is now riddled with conflicts: “I want it this way.” “You take it that way.” “No, no, no.” How do you manage it? I am not asking you to solve such a huge question. I am asking you, where do you see the resistance that would come and is probably already coming to such a vision?

Barnes: Well, there certainly is a lot of it. What do we do about human nature and its multiple contradictions? I guess I skirt around that, frankly. In other words, I do not believe in waiting around until all, or at least a significant majority of humans become enlightened and act differently. I do not believe in waiting for that to happen in order to fix things. I believe it makes more sense to fix the system rather than individuals. Fixing the system could change more people’s behavior faster than trying to change people’s behavior through spiritual, moral or intellectual persuasion. We should make sure that the rules and signals and feedback loops of the system are sufficient to get the outcomes we want. This is kind of a pragmatic way of approaching it, but I think it is deeply American, because if……

Needleman: Deeply American.

Barnes: Go back to the Constitution and the Federalist Papers. James Madison says that humans aren’t angels, and they are not going to be. So we have to set up a political system with checks and balances where all the parts counter-balance each other

Needleman: Balance each other, yeah.

Barnes: And maybe that will keep us from killing each other.

Needleman: It is like they made a distinction there back then between the passions and the interests.

Barnes: Yes.

Needleman: The passions are the strong, physical, emotional, secular, whatever desires, greed, the ego, infidelity, and war and killing and so forth. Let us make it unprofitable to go to war.

Barnes: Yes.

Needleman: And then we deal with the interests, which is for wealth or property, security, that sort of thing. They felt that the interests could be a force against the domination of the passions. I think your vision is somewhere in that direction.

Barnes: It is definitely in that direction. The problem is that our systems need to change. You could look at our Constitution and say, “Well, it worked for a while. It has been going 250 years. Good track record. But maybe it has too many checks and balances, you know. It is coming to a gridlock.” The same could be said about our economic system. Capitalism, as you said earlier, when in its youth it was a great step forward, a great improvement over feudalism. And it has done many things that we like.

Needleman: Yeah.

Barnes: But it hasn’t evolved with the times. And it’s way out of balance now.

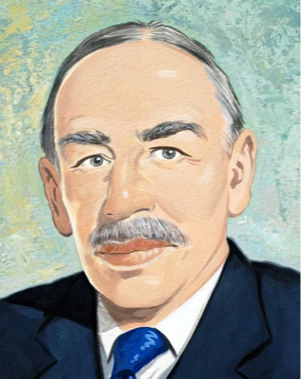

One of the interesting phrases that I am playing with in my book is from John Maynard Keynes’ essay, “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.” He was writing about what the economy could look like a 100 years after 1930 in the era of his grandchildren. And even though this was written in the depths of the Great Depression, with all sorts of havoc about to happen in Europe, he foresaw a future in which the productive capacity of the economy was four to eight times greater than it was when he was writing, and in which what he called the ‘economic problem’ would be solved for many, if not for all. Well, we’ve had a pretty rough ride since 1930, and yet his big prediction is accurate. Our wealth has multiplied many more times than he actually said. And a lot of people do have secure economic lives. I bring that up because it shows that even in the darkest of times, when we don’t see how things can possibly get better, if we think far enough ahead, there is room for a little bit of optimism.

But the other thing Keynes said was that we would see the Euthanasia of the Rentier. Have you ever heard that phrase? It is a charming phrase. His point was that, as the supply of capital grew, its price would fall and the financial sector would shrink. He clearly saw the distinction between the real economy and the financial sector that floats on top of it. But he said that over time the Rentier class would shrivel and die, because the supply of capital would far exceed the demand for it. Well, obviously that hasn’t happened. Quite the contrary. And I have often wondered how the Rentiers pulled that off, given that there is excess supply over demand. And that is a long story, but where I am going is that the problem of rent can be approached in a different way. I mean, it would be nice to put the Rentiers to bed. But another way to approach it would be to make all of us Rentiers and spread financial income around a little more equally.

Needleman: [laughter]

Barnes: I’m going around in a circle here to come back to your original question about what it takes to make humans happy. My thinking is that the economy can make it possible for more humans to be happy, but it can’t make them happy. They have to do that work themselves. But the economy can help by giving people security. Economic security. So they don’t have to spend such a high percentage of their time and psychic energy just struggling to make ends meet. If our economy can minimize the daily struggle and insecurity that goes with living in a crazy capitalist world, where nothing is guaranteed and everybody is out to charge you the most and pay you the least — if our economy can minimize all that stress, then people could work on their happiness a little more. That is my answer to your question.

Needleman: You are saying that the purpose of a government — and an economy, too — is to make it possible for people to become fully human if they wish to. And if they don’t, fine. Go with your houses, your property, don’t worry about it. But it has got to be possible for the other thing. But that is not so easy, because the people who do have power, they want to be the ruler. As Madison said, people are bastards.

Barnes: Yeah. The people who are rich and powerful, the big corporations, the energy companies and the banks, don’t like this sort of thing. Because it shifts money they are extracting from the economy to all of us together. They are sophisticated enough to figure that out. So they fight these ideas.

But there’s another line of resistance, which is more philosophical, where there are a lot of Americans who think, “Giving people money for not doing any work will create a bunch of lazy, no-good bums.” Either that or it is socialism. We in America don’t take money for nothing. We work for it. So that comes up all the time. You may have heard Rand Paul explaining that he was against extending unemployment benefits because, you know, if they got longer benefits they would become moral slouches and it would be horrible for them.

Needleman: Yeah.

Barnes: So for their sake, he was going to deprive them of these benefits. And there are a lot of people in America who think like that. And I don’t know where that comes from. The absolute lack of compassion and the tendency to blame the victim is beyond me. But what I try to show in my book is that the real takers aren’t those who are going to see a doctor under Medicaid or getting food stamps because they lost a job. The real takers are up there on the top. It is just more clever, more disguised, the way they take vast sums of money and say they deserve it because they are “job creators.” We’ve just got to cut through the crap and look at how we have enough wealth in this country to give everybody a basic share of it. It is completely legitimate and it’s not going to turn people into sloths. In fact, the opposite is the case — that with a little bit of economic security, people might well be enabled to pursue less materialistic ways of being happy.

Needleman: Yes, that is just it. It is extremely attractive what you are speaking about. There will be disagreements, obviously. There will be factions. Factions are not so nice a thing. To me, when you have these socio-economic visions which are so appealing, and at the same time without the art of people listening to each other, then it is bound to come to the same old story sooner or later.

Barnes: Well, the way I look at what you just said is through the lens of movements. I think that in order to get major change in any country, certainly this country, you need movements. Strong movements. Now we have had labor movements, civil rights movements, women’s movements, and so forth. And these have produced significant changes. We also have an environmental movement that has produced some progress as well. But at this moment in America’s history, I think the movements have been crushed. The labor movement has been systematically crushed. It used to be 45% of the the private sector workforce and now it is down to 6%. The environmental movement could not pass a climate change bill. And basically, power has concentrated along with wealth.

So we need to build, or rebuild, our movements. And how to do that comes up against the problem you cited. It comes up against the fact that people’s thought processes are very much controlled by large corporate media. And also the fact that the middle-class, which the great majority of Americans are either in or aspire to be in, the middle-class is not really organized at all. Labor unions in effect were a proxy for the middle-class. AARP is another large organization which effectively represents a section of the middle-class, the retired section. But everybody else essentially has no political organization. The middle class is dispersed and voiceless. And until that problem is solved, the corporations that have the power today will continue to wield it. This is a real problem.

Needleman: It is a problem that, I think, should accompany your vision. Even just to make people aware of this. That this is not going to take care of itself. I think there needs to be a community formed that is only interested in truth. Not in wealth, but in truth. And the great thing about America, in my opinion, is that you can search for truth. You still can do it. There is nobody going to kill you for saying most of the things. Some of the things maybe, but not most of them.

Barnes: Well, long may it be so. One of the reasons I started the Mesa Refuge is exactly my belief that truth needs to be sustained and part of doing that is protecting it from government control and distortion and corporate control and distortion. But another part of it is giving ourselves the time and space to see the truth. It takes a lot of effort to break through the noise and actually see the truth. And my hope is that by creating some spaces like the Mesa Refuge, which are very quiet and close to nature, we enable people to see truth and communicate it back to the world.

Needleman: That is really interesting. Thank God you have created the Mesa Refuge. For me, and for my wife Gail, it is been a godsend. But can you communicate this? I saw your talk to Google. I know that audience, I gave a talk there too. Can you weave something of the — not spiritual, I don’t want to use that word — but can you communicate something of the truth element so that, in an audience of a hundred Google engineers, one or two people will be touched? I am just speaking of my own hopes.

Barnes: Well, I don’t remember exactly what happened at that Google event. I don’t recall any such person standing up in the audience afterward. That said, you know, I think the kind of economic system I’m talking about is not inconsistent with a Google vision of the world. In fact, one of the points I make in my book is that the system of paying dividends to everybody from wealth we own together is in some ways analogous to Google, because it can be done electronically. The money comes in and goes out. And it is all basically on computer. You don’t need a government bureaucracy to run this thing.

The way the money comes in would also be somewhat analogous to the way money comes into Google. In Google’s model, people are bidding all the time to buy ads with special words, and they have these continuous little auctions. So it is basically a market setting prices for a finite supply of viewing opportunities. And that market runs itself automatically. People are bidding all the time. Google just takes in the money electronically. And then if you added to that something on the other side that started paying money out to everybody equally as dividends, which of course Google doesn’t do, you would have essentially what I am talking about.

The paying out equally is easy. The hard part is getting it to come in. But the analogy that I like to use is something like a toll road. A toll road is a commons, a shared highway that has a limited carrying capacity. And one way to deal with that is to charge tolls. You may argue freeways are better than toll ways, but leave that aside. My point is that now it is all electronic. You drive across the Golden Gate Bridge and “beep,” your bank account is debited. We can have a system where anytime an oil company sells a barrel of oil with X amount of carbon in it, money comes out of Exxon’s bank account and goes into this common pool. And every month this common pools sends a dividend to your bank account. Setting up a system like this is actually a Google-y kind of thing. So, you know, maybe when I give my next Google talk, I will explain this and they will go “Ooooh!, another profit making opportunity! We can get a contract to run this computer system that distributes wealth equally. Whoopee!” I don’t know.

Needleman: Well. Okay. I think it is still a question of human nature.

Barnes: Well, what do you propose to do about human nature?

Needleman: I don’t have an answer. Or I do have an answer, but it is an answer that needs my view, my hope, and my work is to try to insert it into considerations you are bringing up. I know there are people out there with their knives. Unless there is a fundamental good will in the culture, it is not going to work. I mean, her Majesty’s royal opposition, when it works, is a very honorable thing. People shout and scream and they fight, but that is okay. In a Jewish family, it happens every day. But there is a fundamental lack of good will nowadays. And good will is a necessity if democracy is going to work.

Barnes: I agree. But I also think that human nature is a given. It is not going to change; it is in our DNA. But to the extent there is a solution to it, I think it is sort of self-correcting. In other words, the Republicans have gone beyond the point where I think it is going to work for them. I think there will be a backlash against that “my way or the highway” stuff. At some point it will self-destruct. I mean, it comes and it goes. But I don’t know of any particular other way to do it. Changing the rules a little bit, so you don’t have to get sixty votes to end the debate, for example, and certainly improving campaign financing, those things can help, but the problem will always be there in one way or another.

Needleman: Well, that is very interesting because if that is true, that it is going to self-destruct, there might come a moment in the process when a certain group or person injects something into the process which will prevent it from coming back. A new element.

Barnes: Well, that is exactly my thought. And just to use another historical example, social insurance was started in America in 1935. It started very small and has grown to be about 10% of the economy now with Social Security, Medicare, unemployment and disability. Social insurance is a wonderful thing because it operates outside the regular budgetary process and has been immune to the political dysfunction we’ve been seeing. The model I’ve been talking about with the dividends is a kind of sequel to social insurance. Once it’s set up, it runs itself. It doesn’t need Congress to appropriate money or pass budgets. And it’s a way to unite people. To say that we’re all members of the same society and we have responsibilities to each other and future generations and this is how going to meet those responsibilities and build them into the plumbing of our economic system. Maybe it takes another 10% of GDP, money that is shifted from polluting companies and banks and spread among the people equally. The moment to set that up, to get it started, is precisely what you were saying — when the current dysfunction implodes. That would be the moment to start. And then it would last.

Needleman: Well, I feel like we have just gotten started, but it has been a wonderful start. Thank you so much, Peter.

Barnes: It is been a pleasure, Jerry. I would love to continue off mike or on mike any time.

Jacob Needleman is a professor of philosophy at San Francisco State University and the author of numerous books, including Money and the Meaning of Life, A Sense of the Cosmos, and Notes on the Meaning of the Earth.

Free distribution with attribution

Free distribution with attribution